Wherever They May Roam

Finding the line between independence and vigilance

When I was eight years old, I would sometimes leave the house on my own to walk to a friend’s house. The playdates were pre-arranged, and both sets of parents knew when I’d be leaving, and when I’d be expected.

But that element of risk remained—I’d be walking for probably just over five minutes down a main road, completely on my own, at eight years of age.

At the time, it felt like the first taste of personal responsibility. The beginning of the rite of passage into my teenage years, of sorts. For my parents, it was probably the start of an easier period of their parenting life, where their youngest child was gaining their own independence.

This was the late 90s, and it felt fine. But now, would letting your eight-year-old do this get you into trouble?

What got me thinking about this vague memory from my childhood was this story of a mum from the USA being arrested for “reckless conduct” and “child neglect”, after her ten-year-old son was found to have walked from his home into the local town centre on his own. The mum claims it wasn’t far, he’d done it before, and there was no perceived danger of the area he was walking through. And yet, the law saw it differently.

But would they have left the kid be if he was eleven-years-old? How about twelve, or thirteen? We all know that different kids mature at different ages, and surely fostering independence—within reasonable safety limits—is a good thing. So at what point does nurturing independence become negligent?

Have things really changed?

The world anecdotally feels like a different place for kids to grow up in, depending on which generation you ask. I’m too young to have been a Latchkey Kid—a cultural norm in the 70s and 80s whereby kids would come and go from home as they pleased, often when parents weren’t even there, either with the latch of the house unlocked or with their own set of keys. During the day, kids would just bugger off on their bikes with their mates, apparently to swim in abandoned quarries and get stuck in old fridges, if the public safety adverts of the time were to be believed.

Things weren’t quite so blasé when I was younger—as I said above, I could go short distances but only if it was pre-arranged. The most freedom we had at that young age was to go over the park across the road, but that was only because it was literally in sight of our house.

Now though? I’m not a parent of older children quite yet, but I can imagine what my response would be if my eight-year-old asked if they could go down the shops on their own—and it wouldn’t be in the affirmative.

But why is that? Is it just purely down to cultural and societal shifts, or is there really a greater danger?

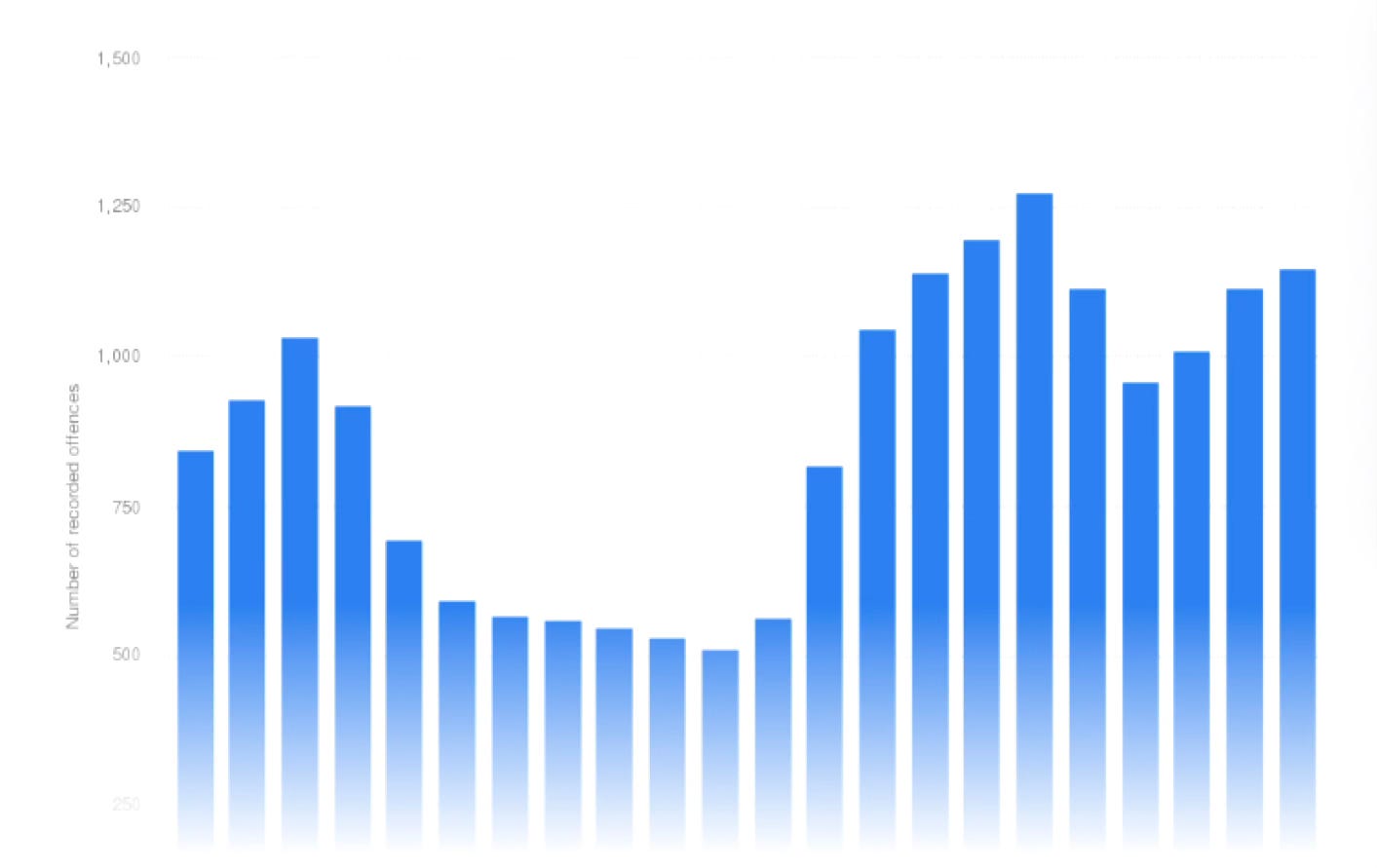

The latest set of data from England and Wales shows a slight increase in the number of child abduction offences compared to the previous year. When also compared across the whole dataset which goes back to 2002/03, there is a noticeable increase since 2015 (although to avoid alarm, the figure relative to other crimes is still very low).

In the USA, it’s estimated that around 460,000 children go missing every year. However, only 0.3% of these incidents involve abduction by a stranger.

It’s only a small amount of data, and some of the numbers seem high and scary. But the risk is still incredibly low for the worst-case scenario incidents that we all fear. In fact, crimes rates generally across the board in most developed countries have trended downwards for decades.

With that, what’s the issue with letting our kids off the leash a little bit?

The case for free-range parenting

There’s a fairly strong case for giving our kids more autonomy. Research published in the Journal of Youth and Adolescence concludes that autonomy-supportive parenting is linked to positive developmental outcomes, highlighting the importance of fostering autonomy in children.

When I visited Japan in 2018, I noticed groups of kids walking around city centres with bright yellow backpacks and school uniforms—without any parent in sight. It’s quite commonplace that schools there encourage—or even mandate—that kids as young as six make the journey to school alone. This isn’t just in rural parts either—I saw kids doing this in Tokyo, a city of over 14 million people.

Sure, you can’t transplant the culture from one country—where it’s expected that the community looks out for these kids as they make their way to school—and expect it to work the same way somewhere else. But it just goes to show what kids are truly capable of when given the opportunity.

Contrast that with the phenomenon of helicopter parenting, which tends to be more prevalent in the West. Research published by the American Psychological Association found that overbearing parenting can hinder children's emotional development, leading to increased anxiety and depression.

If you’re into the idea of ‘free-range parenting’, you may have heard of Lenore Skenazy, who strongly advocates for children to be given more autonomy. The difference in culture between East and West is clear in her case: in Japan, it’s normal for eight-year-olds to catch the subway on their own. When Lenore Skenazy allowed her kid to do the same, she was dubbed “America’s Worst Mom”.

A quote from her book Free-Range Kids that stood out to me was:

You don't remember the times your dad held your handle bars. You remember the day he let go.

This hit hard for me, as the other week was the first time I took my eldest daughter out on a bike without stabilisers. I held her up using a scarf wrapped underneath her armpits and ran alongside, but whenever I loosened that grip slightly, she was giddy with excitement at what she was doing, all by herself. She still talks about it now. Reading that quote and remembering that really resonated with me, and has made me think about how I can be less overbearing.

Following in our digital footprints

But it’s not all one-way traffic in this debate. There is further research that increased parental monitoring does have its upsides.

Another article in the Journal of Youth and Adolescence looked into the effects of parental monitoring on adolescent behaviour, especially around risk. It concluded that effective parental monitoring is linked to a decrease in behavioural problems among adolescents.

Another study, published in the Journal of Child and Family Studies, suggests that higher levels of parental involvement and monitoring are associated with better social skills in some children.

This debate goes beyond the safety of kids walking on the street or taking public transport. One challenge that children growing up in the 80s and 90s never had to contend with was the one place where parents can’t necessarily follow them— the internet.

Having grown up with the advent of social media, I feel like those in my age bracket of 30-35 are pretty savvy with the internet—perhaps more than most—having had to navigate the early pitfalls of online chatrooms and forums for ourselves. Our parents didn’t have a clue what they were. I still remember getting scammed out of my Habbo Hotel password as clearly as it was yesterday. Bastards.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that this generation’s young people are the most clued up about the internet, but recent statistics might hint otherwise. The NSPCC reports an 82% rise in instances of online grooming against children in the past five years, with a quarter of these involving primary school children.

Office of National Statistics data shows that 35% of 10-to-15-year-olds have accepted friend requests on social media from complete strangers within the past year, with 8.5% of those asked having shared their location publicly online.

Again, this is not an area of parenting where I have first-hand experience yet, but this is one particular facet where I will find it hard to not be a bit helicopter-like. We all have anecdotal evidence of how sophisticated online scams are getting. For us dyed-in-the-wool types who’ve been online since the days of MySpace and MSN Messenger, they're fairly easy to spot.

But imagine if you’ve just got your first smartphone, downloaded Instagram or Snapchat and you start seeing the type of adverts or posts that we’re talking about. How would you know how to decipher the scams from the real thing, unless you have the guidance from someone who knows what they’re looking out for?

I remember well the feeling of unease I felt talking to strangers on online chatrooms and forums in my early teens. I wouldn’t have ended up on them if my parents had a clue about the internet, or at the very least I would have known when to stop and what was safe and not safe to do. The only thing keeping me on social media nowadays is the desire to keep up-to-date with what’s going on online, so that I can pass that knowledge and guidance on to my kids when they inevitably end up with an online presence.

A risky business

The wide range of considerations in this debate leaves me stuck betwixt the two camps.

There’s things that I want to do less of when it comes to monitoring the kids as they get older. I made a conscious effort to step away from my eldest a year or so ago whenever she went on climbing frames and the like in the park. I’m not the kind to hover underneath her anymore with outstretched arms. This is in part because I want to take any opportunity I can nowadays to sit down, but also because what good is it doing her? Sometimes life doesn’t come with safety nets.

I’ve felt judged by this before. I’ve seen parents glancing at me as they float around their own little ones, as if to say “are you leaving your child unsupervised?!”

I’m not—I’m managing risk. I can see she might fall from those monkey bars, but I can still see her. The fall isn’t that far. The floor is made of those rubber pellets. I can reach her quickly if she does fall. Plus, the feeling of being able to tackle an obstacle in the park unaided is something she’ll be beaming about the whole way home.

Conversely, I can’t unlearn certain things about the world. Social media in particular is a cesspit of much more than just dogshit opinions. I can’t knowingly expose my children to that kind of stuff. I will hold out as long as I can before letting them loose online, and even then I will make no apologies for using parental controls.

This isn’t a question that I think has a singularly defined answer. Everyone’s idea of risk is different, and is shared by their own experiences and what they therefore want or don’t want for their own children. It’s also shared by where you live and your surroundings. One approach doesn’t fit everyone. As the mother of the young Japanese boy said in the clip I linked earlier, she said she would never let her boy do the same walk to school unaccompanied if they lived in the USA.

But one thing I personally can be sure of is that the mother featured right at the start of the article should never have been placed under arrest. If you’re to class her case as neglect, then you’re tying parents in a straightjacket; basically dictating that they must be able to see them at all times until they’re eighteen.

Recognition should be given to parents who want to give their children that extra bit of autonomy—without putting them at obvious, serious risk. It’s happening already: laws have been passed in the states of Utah, Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, Virginia, Connecticut, Illinois and Montana, guaranteeing that children have the right to unsupervised time without the parents being automatically being considered guilty of neglect.

We can all agree that independence is a positive trait to have in our children. So what’s wrong with a bit more independence for parents too?

Independence or vigilance?

This debate’s much more complex than just a binary choice between letting your kids out at all hours, versus wrapping them in bubble wrap until they’re 30. My opinion is still forming on the subject, seeing as my eldest is five-years-old and still needs a fair amount of supervision. So this is one that I’m really keen to hear your views on, especially those with slightly older kids than mine. Let me know what you think!

Previously on Some Other Dad

Shitting Myself About a Magic Trick

This story, as most of mine do, starts with a bit of childhood nostalgia.

Ooof this is one I have thoughts on.

My friend and I got a talking to by a security guard the other day because our children (aged 6-8) were unsupervised outside the library... in a safe grassed area between the library and the playground, away from the carpark, and in full view because of the glass windows. We were in the process of packing up our stuff and our younger kids to join them.

It's so hard to give our kids more independence! Not because I'm afraid of my kids getting hurt, lost, or abducted. But because I'm afraid of well-meaning people telling them off (it's happened when my 5 year walked home from the park, 3 houses away and a stranger stopped their car to ask him where his parent was), calling the police, or otherwise meddling. I know what my kids are capable of, but I can rarely give them that independence. It's so sad

I enjoyed reading this and have had many similar thoughts and feelings.