Paternity Pending

Two weeks ain't cutting it, mate

December is a really busy time for us parents. Buying and wrapping Christmas presents, rifling through the attic for the decorations, navigating all the Christmas-related school admin—it’s no joke.

This is my excuse for not having a fresh new issue ready this week. But do not fear, dear reader—I’ve delved into the archive and pulled out this issue about paternity leave which was very popular at the time.

And, unfortunately, is still as relevant as it was a year and a half ago.

As I mentioned at the end of last week’s post, my paternity leave has come to an end. I blearily rolled out of bed and into my office last Thursday, dusted off the ugly corporately-assigned laptop and turned on the work phone. The time has gone impossibly fast, and mentally, I’m nowhere near ready to turn my attention back towards the day job (or the 982 unread emails in my inbox)—but somehow I’ll have to make myself ready.

In truth though, I’m kind of still on leave. On top of the three weeks paternity leave I get from my employer and the week of annual leave I took to top it up to four weeks, I’ve used some of my leave to shorten my work hours for the next few weeks, which means I’m not back to full-time until July. It’s far less jarring this way around than jumping two-footed into the deep-end like I did last time, when I took five weeks (three weeks, plus two of my own leave) and then went straight back.

But something that unites my two periods of paternity leave over the past four years is that whenever anyone would ask what time I was taking off and I’d tell them, they’d always say “Oh that’s a good amount of time”, or “That’s generous”.

When I first heard that, I thought “Is it?”

I remember hearing tell of countries, mainly in Scandinavia (seriously, they’ve got everything sussed), where fathers could get way more than the three weeks I was being offered. With this portion of paternity leave, and the inevitable questions about how long I was taking, once again my mind turned towards the Nordic utopia, and how much better their provisions are for parental leave.

But I realised that I’d never actually looked into what exactly they did get. So this is what I found, and here’s some of the best:

Sweden - both parents get 480 days between them—90 of which are exclusively for each. These are paid at 80% of their normal pay.

Estonia - 435 days off between the two partners, with pay set at the average of their two salaries.

Norway - fathers get up to 10 weeks, depending on their wife/partner’s income. On top of that, parents get an extra 46 weeks at full pay—or 56 weeks at 80% of their normal pay.

South Korea - although this one is new and compensation hasn’t been confirmed, plans are for both parents to get 18 months leave each.

Spain - Recently increased to 16 weeks—on par with maternity leave in the countries—on full pay.

After reading about these countries, and realising how it’s not just the Scandinavians and the Baltics being generous with their paternity leave, I felt somehow vindicated at not feeling as though my three weeks was sufficient. Especially as only two of those weeks are government-approved—the extra week is only because of my employer.

That two weeks in the UK is also paid at a pretty miserly rate: either £149 (around $195) a week, or 90% of your weekly pay—whichever is lower. And if you’re self-employed, a contractor or otherwise not on some kind of formal payroll, you’re shit out of luck.

According to the above graph from a UNICEF report in 2019 (although most of the data in the graph is from 2016/2017), the UK is certainly in the lower half of the “richest countries” for provision of paternity leave. But as you can see, there’s a few countries with provisions even lower than that. Let’s talk about a few of them:

USA - Dads in America don’t get any paternity leave guaranteed. There is some provision under the Family and Medical Leave Act, but it’s unpaid and not everyone gets it. What’s wild about the USA though—and as the majority of my readers are American, you’ll probably already know—is that there’s no guaranteed maternity leave for mothers either.

Australia - Australian dads can get a slice of the 18 weeks parental leave, paid at minimum wage, but only if transferred from the mother’s allowance, as it automatically is allocated to her.

Mexico - Officially, dads in Mexico can get just five working days of leave, paid at full pay. However, as pointed out above, as up to 60% of men in the country work outside of the formal economy, they’re missing out.

You may notice Japan right at the top of that list, offering a full 52 weeks paternity leave to new dads, and you might wonder why I didn’t talk about them above. Well, the UNICEF report also highlights that in 2017, less than 5% of men eligible for paternity leave actually took it.

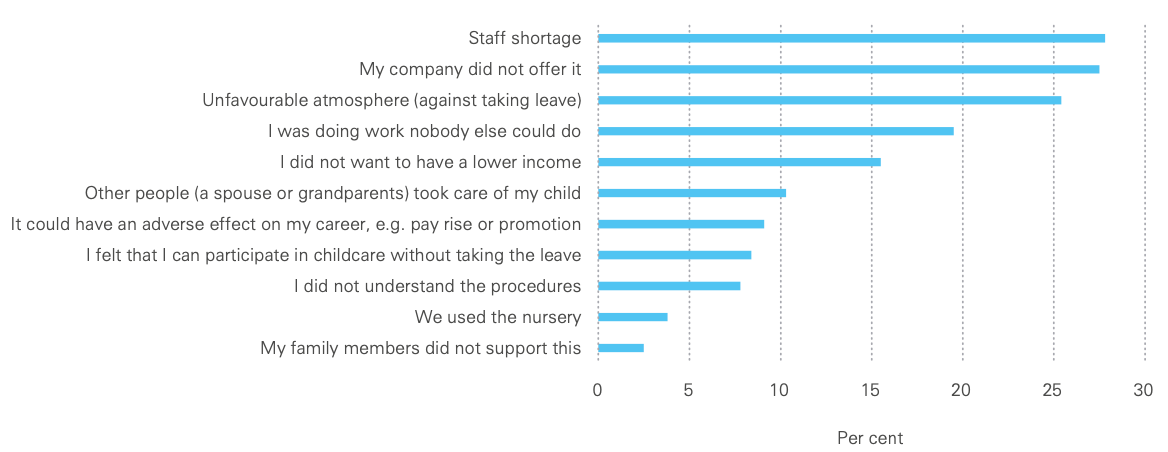

The top three reasons for this—staff shortages, companies not offering it, and “unfavourable atmosphere”—all speak to another issue that affect dads’ ability to take the leave they’re due: culture. I know anecdotally that this isn’t just the case in Japan, either—a good few friends of mine who work in fairly demanding industries felt pressure to take as little leave as possible, despite their employers’ own policy.

I already knew that the USA was among those countries not offering anything in terms of paternity leave—aside from what employers might offer—but I was really surprised to find so many developed countries with offerings under two weeks—which seems to be a threshold that a lot of countries aim for when deciding on paternity leave.

But any dad that’s had to roll out of bed after another sleepless night and leave their partner with the baby on their own—knowing that they might well not be able to go to the toilet, shower or do basically anything for themselves all day—will attest that this two-week mark that many countries seem content with is not enough.

You may be familiar with the three trimesters of pregnancy, each lasting roughly three months. But the fourth trimester is a thing as well. Those first three months for a baby outside of the womb are—to put it bluntly—a massive headfuck, especially for someone without a fully developed brain. You’re no longer being rocked endlessly by the movement of your mother’s diaphragm, your ears are no longer full of the lovely lilt of your mother’s heartbeat, and there’s an endless queue of nans and aunts waiting to plant a smacker on your unblemished skin1. It’s no wonder they cry more during these three months than at any other time.

So it’s no wonder either that this is the period where parents feel like they need their village the most—let alone their other half.

I could rant for hours about this—to me, the fact that in the richest countries in the world, we expect (mostly) mothers to put up with the most intense2 period of parenting on their own, all whilst they’re most likely dealing with constant bleeding, hip pain, stitches, or even recovery from a C-section—the only medical procedure that cuts through six layers of skin, fat and muscle. For a society has so many parents in it, and relies on people deciding to have children to keep the wheels of modern civilisation moving, it’s crazy to me just how unseen the struggles of new parents are. Once everyone’s had their selfies and cuddles with the smushy little newborn, it’s like society couldn’t give a fuck anymore.

Mothers deserve to have their partners around for those three months if that’s what they feel they need—and there’s plenty of dads out there who want to be there for their family for longer.

I don’t doubt that policies like those in South Korea would cost an eye-watering sum to implement in the US or the UK. I’m not here calling for a years’ fully paid leave. But the standard two weeks or less that a lot of first-world countries seem to think they can get away with offering is not good enough.

Three months—fully paid or not—is where we should be setting the bar for enabling both parents to be where they need to be—at home setting the foundations of their new family.

How much leave dads are able to take shouldn’t be up to the benevolence of corporations—many of whom are to blame for harbouring cultures like those we see in Japan that makes men not feel comfortable taking the paternity leave they’re entitled to. Every dad should have the right to adequate leave, and the only way to square that is through government action.

Until then, all I can do is call for all dads reading this to take what you’re owed. Do not let workplace or cultural pressures keep you from your instinct to be there for your family when they need you most.

Over to you

The provision of paternity and maternity leave is so dependent on so many factors—it’s hard to meet two different people with the same experience. I’d be really interested to know how long you were able to take, and whether you felt any pressures to take less or return sooner than you’d have liked.

Previously on Some Other Dad

Do not hesitate to deny anyone the chance to kiss your baby. Regardless of who they are, they have no automatic right to do so.

Note that I don’t say “hardest”—every stage of parenthood has its own unique challenges that mark them apart from the others. But I feel comfortable saying the first three months are the most intense.